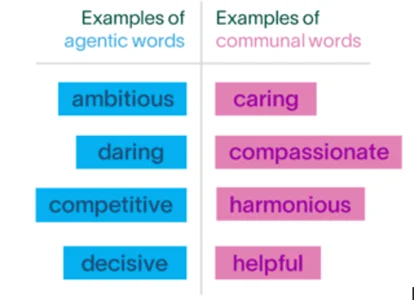

The agentic-communal model of advantage and disadvantage is the base of our solution. This model is critical when discussing inclusive language. Western societies value agentic traits more than communal values, which advantage demographics like men, white people, and younger professionals. In consequence, we associate them, and they self-identify with agentic traits. Women, marginalised ethnic groups, and older, neurodivergent or professionals with disabilities are disadvantaged. We associate them, and they self-identify with communal characteristics [1].

Studies have shown that gender affects people’s evaluation disparately, affecting their work performance [2], potential [3], and likeability [4, 5, 6]. The agentic wording in job ads discourages women from applying, while the communal language has some tendential effect on male applicants [7, 8].

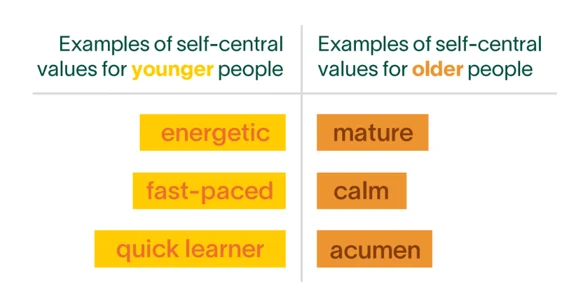

We associate the agentic/communal language differently with people based on age. The communal traits are more associated with older people [8], while the agentic qualities are more associated with and self-central to younger people [9, 10, 11]. Researchers have also found evidence of that distinction cross-culturally [12]. Agentic language can also discourage neurodivergent applicants and people with disabilities [12].

Finally, using language to target marginalised candidates does not erase stereotypes nor spread inclusivity. Quite the opposite – it can reinforce social stereotypes about the position you are recruiting for [5, 6, 13, 14].

We continuously research and use validation techniques such as behavioural studies and country and language-specific word embedding methods. Through such means, we ensure that the language used in our software is inclusive and effective.

[1] Rucker, D. D., Galinsky, A. D., & Magee, J. W. (2018). The Agentic–Communal Model of Advantage and Disadvantage: How Inequality Produces Similarities in the Psychology of Power, Social Class, Gender, and Race. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (pp. 71–125). Elsevier BV. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aesp.2018.04.001

[2] Akos, P., & Kretchmar, J. (2016). Gender and Ethnic bias in Letters of Recommendation: Considerations for School Counselors. Professional School Counseling, 20(1), 1096-20.1. https://doi.org/10.5330/1096-2409-20.1.102

[3] Madera, J. M., Hebl, M. R., & Martin, R. C. (2009). Gender and letters of recommendation for academia: Agentic and communal differences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(6), 1591–1599. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016539

[4] Koenig, A., & Eagly, A. H. (2005). Stereotype Threat in Men on a Test of Social Sensitivity. Sex Roles, 52(7–8), 489–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-3714-x

[5] Heilman, M. E., Wallen, A. S., Fuchs, D., & Tamkins, M. M. (2004). Penalties for Success: Reactions to Women Who Succeed at Male Gender-Typed Tasks. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(3), 416–427. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.3.416

[6] Schneider, A. K., Tinsley, C. H., Cheldelin, S., & Amanatullah, E. T. (2010). Likeability v. Competence: The Impossible Choice Faced by Female Politicians, Attenuated by Lawyers. Duke Journal of Gender Law & Policy, 17(2), 363–384. https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1179&context=djglp

[7] Gaucher, D., Friesen, J. P., & Kay, A. C. (2011). Evidence that gendered wording in job advertisements exists and sustains gender inequality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(1), 109–128. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022530

[8] Gebauer, J. E., Wagner, J., Sedikides, C., & Neberich, W. (2013). Agency-Communion and Self-Esteem Relations Are Moderated by Culture, Religiosity, Age, and Sex: Evidence for the “Self-Centrality Breeds Self-Enhancement” Principle. Journal of Personality, 81(3), 261–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2012.00807.x

[9] Posthuma, R. A., & Campion, M. A. (2009). Age Stereotypes in the Workplace: Common Stereotypes, Moderators, and Future Research Directions†. Journal of Management, 35(1), 158–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308318617

[10] Kite, M. E., Stockdale, G. D., Whitley, B. E., & Johnson, B. T. (2005). Attitudes Toward Younger and Older Adults: An Updated Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of Social Issues, 61(2), 241–266. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00404.x

[11] Ali, H., & Davies, D. R. (2003). The effects of age, sex and tenure on the job performance of rubber tappers. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 76(3), 381–391. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317903769647238

[12] Boduroglu, A., Yoon, C., Luo, T., & Park, D. C. (2006). Age-Related Stereotypes: A Comparison of American and Chinese Cultures. Gerontology, 52(5), 324–333. https://doi.org/10.1159/000094614

[13] Bavishi, A., Madera, J. M., & Hebl, M. R. (2010). The effect of professor ethnicity and gender on student evaluations: Judged before met. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 3(4), 245–256. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020763

[14] Hester, N., Payne, K. B., Brown-Iannuzzi, J. L., & Gray, K. (2020). On Intersectionality: How Complex Patterns of Discrimination Can Emerge From Simple Stereotypes. Psychological Science, 31(8), 1013–1024. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620929979

Balandin, S., Crosbie, J., Zammit, J., & Williams, G. (2018). Employer engagement in disability employment: A missing link for small to medium organisations – a review of the literature. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 48(3), 417–431.https://doi.org/10.3233/jvr-180949

Fraser, R. J., Johnson, K. L., Hebert, J., Ajzen, I., Copeland, J., Brown, P. A., & Chan, F. (2010). Understanding Employers’ Hiring Intentions in Relation to Qualified Workers with Disabilities: Preliminary Findings. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 20(4), 420–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-009-9220-1

Harder, J. A., Keller, V. N., & Chopik, W. J. (2019). Demographic, Experiential, and Temporal Variation in Ableism. Journal of Social Issues, 75(3), 683–706. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12341

Ju, S. Y., Roberts, E. M., & Zhang, D. (2013). Employer attitudes toward workers with disabilities: A review of research in the past decade. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 38(2), 113–123. https://doi.org/10.3233/jvr-130625

Maass, A., D’Ettole, C., & Cadinu, M. R. (2008). Checkmate? The role of gender stereotypes in the ultimate intellectual sport. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38(2), 231–245. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.440

Mahalik, J. R., Morray, E. B., Coonerty-Femiano, A., Ludlow, L. H., Slattery, S. M., & Smiler, A. P. (2005). Development of the Conformity to Feminine Norms Inventory. Sex Roles, 52(7–8), 417–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-3709-7

Patton, E. (2019). Autism, attributions and accommodations. Personnel Review, 48(4), 915–934. https://doi.org/10.1108/pr-04-2018-0116

Pavelko, R. L., & Myrick, J. G. (2015). That’s so OCD: The effects of disease trivialisation via social media on user perceptions and impression formation. Computers in Human Behavior, 49, 251–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.02.061

Rudman, L. A., & Phelan, J. E. (2010). The Effect of Priming Gender Roles on Women’s Implicit Gender Beliefs and Career Aspirations. Social Psychology, 41(3), 192–202. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000027

Steele, D. (2018, February 14). Crazy talk: The language of mental illness stigma. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/science/brain-flapping/2012/sep/06/crazy-talk-language-mental-illness-stigma

Steele, J. L., & Ambady, N. (2006). “Math is Hard!” The effect of gender priming on women’s attitudes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42(4), 428–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2005.06.003

Trauth, E. M., Cain, C. C., Joshi, K., Kvasny, L., & Booth, K. M. (2016). The Influence of Gender-Ethnic Intersectionality on Gender Stereotypes about IT Skills and Knowledge. Data Base, 47(3), 9–39. https://doi.org/10.1145/2980783.2980785

Vilchinsky, N., Werner, S., & Findler, L. (2010). Gender and Attitudes Toward People Using Wheelchairs: A Multidimensional Perspective. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 53(3), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034355209361207

Wilding, M. W. (2018, November 14). I’m a professor of human behavior, and I have some news for you about the “narcissists” in your life. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.in/strategy/im-a-professor-of-human-behavior-and-i-have-some-news-for-you-about-the-narcissists-in-your-life/articleshow/66626129.cms

Wille, L., & Derous, E. (2017). Getting the Words Right: When Wording of Job Ads Affects Ethnic Minorities’ Application Decisions. Management Communication Quarterly, 31(4), 533–558. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318917699885

support@developdiverse.com